The massive methane gas leak in Southern California, which seeped natural gas into Los Angeles county air from late October to early February, is officially the worst methane leak in U.S. history, according to a new study in the journal Science.

Before it was sealed on Feb. 11, the well blowout at the Aliso Canyon underground storage facility owned by the Southern California Gas Co. emitted close to 100,000 metric tons of methane, a potent greenhouse gas. While methane is considered benign toward human health, the report conducted an independent survey of other hazardous chemicals, such as benzene, which also can be released during a well blowout.

Concerns over these chemicals — and the long-term environmental ramifications of such a leak — remain for the 4,000 displaced households of Porter Ranch, who lose funding for the temporary housing provided by Southern California Gas Co. today. Los Angeles attorneys are seeking an extension of the temporary housing.

How do scientists know that Aliso Canyon was the biggest methane leak on U.S. soil?

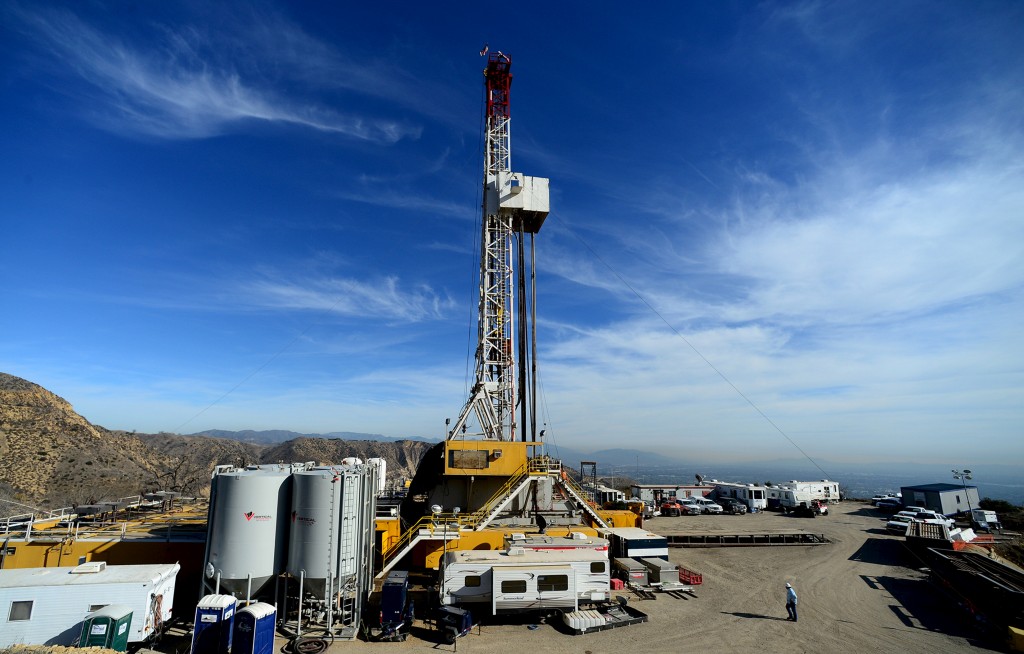

Crews from Southern California Gas Company and outside experts work on a relief well at the Aliso Canyon gas field above the Porter Ranch section of northwest Los Angeles, California. Photo by in this December 9, 2015 Dean Musgrove/Reuters

The Aliso Canyon leak was detected on Oct. 23, and two weeks later, atmospheric scientist Stephen Conley received a call from the California Energy Commission. Conley heads Scientific Aviation, a company with high-tech planes built for analyzing the chemical composition of the atmosphere. He had been contracted by the commission to monitor pipeline emissions.

“So on Nov. 7, they said, ‘Hey, can you forget your pipeline flight today, go to L.A. and measure this?’ And because they did that, the world now knows the size of this leak,” said Conley, who is a lead author on Thursday’s report.

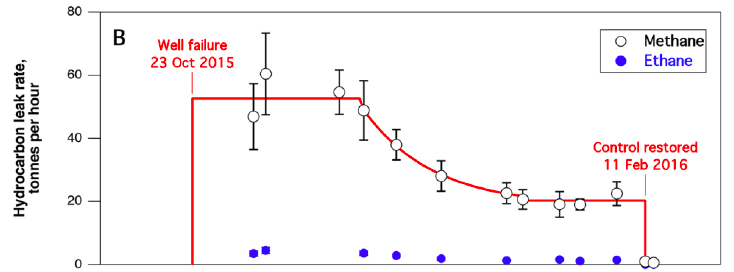

Since then, Conley has made 13 research flights at regular intervals to monitor the leak. During the first six weeks, the blowout released about 53 metric tons per hour of methane, the primary component of natural gas, and also 3.9 metric tons per hour of ethane. This rate of release is on par with methane emissions from some of the biggest oil-gas fields in the country, including Barnett shale in Texas (76 metric tons per hour), Haynesville shale in Arkansas (80 metric tons per hour) and the northeastern Marcellus shale in Pennsylvania (15 metric tons per hour). Aliso Canyon still registered the highest total because of the four-month period of the leak.

“When the gas company started preferentially draining that reservoir, what you see is this beautiful decline every single time [in the data], until it reaches the levels seen in the middle of January, when they stopped draining the reservoir,” Conley said.

Methane (black outlined circles) and ethane (blue) leak rates from airborne measurements near Aliso Canyon. Red line is a fit to the airborne methane data, assuming an average leak rate from blowout to December 4. There was an exponential decrease from then until early January as the SoCal Gas company drained the reservoir. The leak rate leveled off, as a minimum pressure was maintained in the reservoir to serve Los Angeles customers. This leakage was maintained until February 13, when the well was sealed. Photo by Conley et al., Science (2016)

At its peak, the Aliso Canyon leak doubled the methane emissions rate for the Los Angeles Basin and was the biggest known source of this greenhouse gas in the country. Its leak rate was twice that of the next largest man-made source of methane in the U.S., a coal mine in Brookwood, Alabama, which releases methane as part of its normal operations.

In total, the leak discharged 97,100 metric tons (5 billion standard cubic feet) of methane into the air, topping the former U.S. record holder: a 2004 blowout from an underground storage facility in Moss Bluff, Texas. That incident released 6 billion standard cubic feet of methane, but most of it was consumed by a subsequent fire and immediately converted to carbon dioxide.

Did the leak start before Oct. 23?

A neighborhood where many people have left their homes because of a massive natural-gas leak is seen in the Porter Ranch neighborhood of the of the San Fernando Valley region of Los Angeles, California, on December 22, 2015. Photo by David McNew/AFP/Getty Images

It’s possible, but impossible to prove with the current data, Conley said.

The Aliso Canyon storage facility is the fourth largest of its kind in the U.S. In 2014, it accounted for 2.1 percent of the total U.S. natural gas storage in 2014.

That leak could have gone on for a long time without running out of gas, Conley said, and methane leaks at these types of facilities aren’t unusual.

“There are leaks every day, every storage facility that we go to has leaks, but I don’t have any data to suggest that it did or didn’t start before Oct. 23. I can’t even speculate on that,” he said.

Methane and ethane aren’t hazardous to humans, but did the leak release other dangerous gases?

Residents of the Porter Ranch area of Los Angeles hold up signs related to a gas leak in their community during the meeting of the California Air Quality Management District in Granada Hills, California Jan. 9. Photo by Danny Moloshok/Reuters

Benzene is a human carcinogen, and trace levels of this compound are found in natural gas. A preliminary study by the South Coast Air Quality Management District found that benzene levels in the Porter Ranch Estates neighborhood sat at 3.7 parts per billion on Nov. 10, which was seven times higher than the normal range for the Los Angeles area (0.1 to 0.5 parts per billion). However, by late December, two months after the blowout, benzene levels in Porter Ranch fell within the regular range.

At the hilltop source of the leak, a mile away from Porter Ranch, benzene levels were 10 times higher than normal, reaching 5.6 parts per billion on Nov. 10, according to the Southern California Gas Co.

Leaky gas well SS-25 in Aliso Canyon and the town of Porter Ranch as seen from Stephen Conley’s aircraft during an emissions survey. Photo by Stephen Conley

The findings released Thursday reaffirmed the idea that there was a steady release of benzene near the well in late December, while levels in Porter Ranch remained low.

“I suspect if you were standing up on top of the hill, then it would probably have been unhealthy,” said University of California atmospheric chemist Donald Blake, who is a co-author on the study in Science. “ We can say the leak elevated the amount of benzene in Porter Ranch to around 1 part per billion. Background benzene in L.A. is around 0.1 parts per billion. So it would have increased the benzene, but not to levels that I think are of great concern.”

The health ramifications, however, remain a matter of debate. The South Coast Air Quality Management District has said that the blowout increased the cancer risk by less than two people in a million. California’s Environmental Protection Agency defines hazardous benzene levels as 8 parts per billion for a one-hour exposure and 1 part per billion for chronic exposure (eight hours or more). Meanwhile, the World Health Organization states that there is no safe level of benzene exposure, given it’s a known carcinogen.

There also are worries surrounding the release of smelly sulfur-based compounds.

“People’s nausea, headaches and feelings of malaise were likely because of the sulfur compounds,” Blake said. On Nov. 12, the California Office of Environmental Health Hazard Assessment recorded one extreme instance in Porter Ranch, where levels of hydrogen sulfide levels were six times higher than what’s deemed safe for acute exposure. However, this reading might be an outlier, given high levels of hydrogen sulfide weren’t subsequently recorded.

Is the Aliso Canyon leak going to aggravate global warming?

“This is a question that everybody seems to be asking: Is Aliso Canyon going to make some noticeable change to the global climate,” Conley said. “And the answer is no.”

Sure, the leak was a “monster,” he said, but it represents a drop in the bucket. For example, even though the leak will likely account for 25 percent of Los Angeles’ methane emissions this year, it will represent only 9 percent of the state’s methane emissions.

People instead should be concerned about all of the emissions causing the global temperature to rise, said Conley. And they should demand faster responses when a major leak is detected, including deciding beforehand which agency is responsible when a blowout occurs and employing more regular surveillance of oil and gas facilities, he said.

“We should have mechanisms in place so that when the next Aliso Canyon event happens, someone’s measuring it within hours, not weeks. We missed the first two weeks of this.”

ncG1vNJzZmivp6x7sa7SZ6arn1%2Bjsri%2Fx6isq2ejmLamusKeZqWno2Kur7PEpZysZZ2awamtzZ5kpZ2RoHqqv4yonZ%2Bhk56urbjYZquhnV2svLO%2F02agp2WlYsButMisq6iqqQ%3D%3D